02-09-2020

Marbella (Costa Rica): chronicle of a coastal conflict

Arturo Silva Lucas | Alba SudThe community of Marbella, in the canton of Santa Cruz, Guanacaste, is the latest conflict in the coastal areas of Costa Rica. The recent lawsuit of the Costa Rican Federation for the Conservation of the Environment (FECON) before the municipality raises the scale of the conflict.

Photography by: Image of Arturo Silva.

Marbella is the most recent conflict in the province of Guanacaste, Costa Rica. The community located on the southernmost coast of the canton of Santa Cruz synthesizes the problematic relationship between real estate tourism developments and coastal communities. The loosely regulated growth of condominiums and second homes has once again put pressure on water and public domain spaces such as the maritime land zone (ZMT).

The community is torn between replicating the residential tourism model seen in other Guanacaste beaches or, on the contrary, propose alternatives for coastal development. With an uneven balance of forces, real estate developers have had the liberty to impose their interests. The none or little institutional concern, together with meddling in community affairs has allowed the real estate agenda to prevail over the rest of the community.

What is happening?

The community of Marbella is located between Tamarindo and Nosara, two of the most popular tourist destinations in Guanacaste. It has a population of fewer than 200 families (CCSS, 2016). The low population density, its geographic location, added to attributes such as a long coastline and scenic beauty, are a magnet for coastal real estate investments.

The community entered the investor's radar during the real estate tourism explosion in the mid-2000s. Despite having started the first investment cycle almost twenty years ago, it has not yet closed. Marbella exemplifies not only how residential tourism invades pristine destinations, but also shows what resources are in dispute when the territory has not yet been fully reconverted.

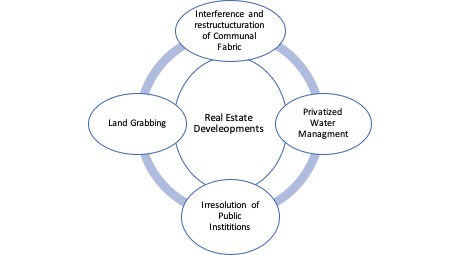

Taking Marbella as an example, the first cycle of real estate investments is characterized by 1) an accelerated process of land grabbing by real estate agencies; 2) private control of water to supply residential use; 3) Irresolution of public institutions and 4) Interference and restructuration of communal fabric.

While the first two go hand in hand, the latter becomes evident once there is an obvious intention to invest in large residential complexes. It is in this context that two real estate groups have been protagonists of the community in recent years. The first is Marbella Group Developers, chaired by Jeffrey Allen, owner of the Posada del Sol, Vista Bella, Ruta del Sol, Costa Dorada, and the Tikki Hutt restaurant located in ZMT. The second real estate group is Dbio Developers, which oversaw the construction of Lomas del Sol and Jardines del Sol, and on whose behalf Antonio Marvez acts. Both are the subject of complaints filed with the Costa Rican Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers (AyA), the Municipality of Santa Cruz, the Constitutional Court, the Public Ministry, and the Environmental Prosecutor's Office of Guanacaste.

This article is the result of the follow-up that has been given to the case in the last two years. Throughout this time, information has been collected through documentation and testimonies from neighbors who for various reasons prefer to remain anonymous, at least until institutions and local governments take a defining position in the conflict. We proceed to describe each of the mentioned characteristics supported by the information collected.

Land grabbing by real estate agencies

Possession of land is necessary to start the construction of residential complexes. The change from rural to urban land occurs through the sale of parcels owned by local inhabitants at the hands of real estate agencies. On July 28, one of those local inhabitants, with more than 60 years of living in Marbella, told us that the first lots were sold at the end of the nineties for between $ 1 and $ 5 per square meter. Today, once real estate agencies have taken ownership of the land, the resale value ranges from $ 70 to $ 100 per square meter.

The concentration of large areas of land in a few hands is a key requirement to control the price in the real estate market. Due to the speculative nature of residential tourism, the promise of investment is many times greater than what has actually been built. It is estimated by the local inhabitants that the land owned by Marbella Group Developers can be more than a thousand hectares, the majority without construction, others still without finishing and, to a lesser extent, completed residential complexes.

In Marbella, the ZMT is also under real estate pressure. The ZMT is the public domain through state property, is made up of the first 200 meters from high tide. The last 150 meters, although they can be given in concession by a vote of the Municipal Council, must prevail environmental criteria that respond to a benefit for the canton and the communities.

There are currently two cases that are under investigation. The first has to do with the Tikki Hut restaurant, owned by Jeffrey Allen, the construction of roads, and electric lighting at ZMT. Over the past two years, residents and other organizations have repeatedly consulted the Municipality of Santa Cruz to explain what criteria have been used for the existence of roads, electric lighting, and private business in the ZMT.

Detail of the Tikki Hut restaurant and built roads.

The second case is an independent investigation carried out by the Attorney General's Office (PGR), the entity in charge of looking after state assets. As detailed in file 18-3974-1027-CA, in the ZMT of Marbella, 19 registry plans have been titled to private names, violating the principle of public interest. The size of the titled lots ranges between half and two hectares. The state land recovery process has been interrupted by the impossibility of notifying all the holders. Some do not reside in Costa Rica and other lands are in the name of dissolved public-limited companies. Once the hearing period begins, it is intended to know how this land could be registered, that by administrative principle is not subject to sale and purchase, and who is involved.

In both cases, the first institution pointed is the Municipality of Santa Cruz. As the cantonal administrator of State assets is its responsibility to ensure the protection of lands of public domain. Secondly, it can be questioned whether the construction permits granted in ZMT really obey the general interest, otherwise the legal principle of “lesividad” in public administration would be violated.

But the control of land for tourist-residential purposes is not enough if abundant drinking water quotas are not guaranteed. The water needs are not only for domestic use but also for gardens, common green areas, swimming pools, and other amenities that are part of the menu that real estate agencies offer to second residents in these destinations. Hence, it is especially important to know how the community's water has been managed.

Private control of water to supply residential

Water management was the first edge through which the conflict in Marbella became noticeable. The intention to privately manage drinking water was made possible by the existence of illegal wells or by fraudulent management of rural aqueducts (ASADAS) (1).

Antonio Marvez, in charge of the Lomas del Sol and Jardines del Sol residential complexes, is currently being investigated for the crime of usurpation of water by the Guanacaste Environmental Prosecutor's Office. This is stated in the file 17-001221-0412-PE of the Prosecutor's Office. He is charged with supplying water through illegal wells within the aforementioned residential complexes. Classified as a criminal offense by the Costa Rican legal system is still awaiting the first hearing. In recent statements to the press, the legal director of AyA, José Miguel Zeledón, affirmed that apart from the crime charged, this type of infraction usually points to other offenses, such as the use of false documentation and corruption in municipal construction permits. As a precautionary measure, Marvez was prohibited from continuing to extract water from illegal wells, although there is no certainty that the measure is being carried out.

Entrance of the residential. Image of Alba Sud.

For his part, the American citizen Jeffrey Allen chose to grant himself and his residential projects water availability permits. This was possible because Allen came to preside at the same time the ASADA of the community, ASADA Marbella, and a second ASADA, that of Posada del Sol. The first was presided over from 2007 to 2015, and the second from 2009 to 2019. Presiding two ASADAS is not a violation of the rural aqueduct administration law, what is pointed out is that Allen provided letters of availability of water without technical support to projects and companies in which he was involved.

For our part, we have a copy of an official letter dated April 18, 2017, where the board of directors of ASADA Posada del Sol granted a letter of water availability to one of the properties, precisely in Posada del Sol, without further technical detail. Finally, in a formal complaint against Jeffrey Allen, AyA requested the intervention of ASADAS Marbella and Posada del Sol in the face of the accumulation of complaints from users of the service.

In the criminal complaint, of which a copy is also available, delivered to the Santa Cruz Prosecutor's Office on March 11, 2019, it is detailed how Allen operated through networks of public-limited companies and front men for his own benefit. The possible crimes that AyA indicates are eleven, among which the most serious are those of illicit enrichment, influence peddling, use of false documents, and concealment of assets against the Treasury.

In a solution that does not end up satisfying the entire community, AyA has chosen to directly manage the water in Marbella. This is a decision already seen in other coastal communities with similar conflicts, whereby the administration of the resource ceases to be community-based and becomes centralized in AyA.

In Costa Rica, and of course Guanacaste, community groups, and neighborhood associations are the main actors that have questioned the inadequate management of natural resources. These groups tend to seek an institutional solution to conflicts (Alpízar, 2019), so it is necessary to know what response there has been from the different institutions that have participated so far.

The irresolution of public institutions

The accusations against Jeffrey Allen and Antonio Marvez are in the hands of the Judicial Power, and follow the due process when it comes to criminal complaints. As in other countries, the administration of justice in Costa Rica is slow pending the first hearings. Here we are interested in the role that public institutions have had in managing the conflict and how this has allowed the path to be level for the indicated developers.

In the first place, AyA for being the main governing body in water matters, either by providing service directly or by delegation principle with ASADAS. In the case of Marbella, the change in the administration of the water resource to AyA seems that it has not interrupted the satisfaction of the service to real estate developments. Residents of the community have reached this conclusion, who affirm that the number of residential residents has not had great variations since the institution manages the water.

During an extraordinary meeting held on May 20, 2020, the AyA board of directors, in the exercise of self-criticism, mentioned the fact that, despite having the legal authority to take over water management from the ASADAS, does not have the capacity to resolve conflicts. Specifically cites the case of Marbella:

There are many interests and we have been trying to organize those private projects that were established about 10 years ago and that is almost on the loose: the case of Marbella, for example, which we took on but it has not yet been easy to solve. (EXTRAORDINARY ACT 2020-29, 2020, p.9)

Throughout the act, it's reaffirmed that it is AyA's priority to strengthen community water management through ASADAS, since they are the first beneficiaries of the service. However, the case of Marbella goes in the opposite direction. This raises the urgency of asking whether centralizing the service really solves the conflict. What we do see in Marbella is that the usufruct of real estate developers, the result of strategic control of water, outside of the law for more than 10 years, has no major consequence. The change in the provision of the service did not interrupt the flow of water to the real estate projects, which from the beginning was illegal.

As for the ZMT, the Municipality of Santa Cruz sins of not having the capacity to respond to the questions that have been made. Since 2018 they have been repeatedly consulted to determine with topographic measurements if the road, electric lighting, and the restaurant owned by Jeffrey Allen are illegally in the ZMT. The request for studies was initially made by the local non-governmental organization Marbella Verde.

The first one in August 2018, later and due to the absence of a response, an appeal was filed to the Constitutional Court. In resolution No. 2019014390 the Court declares the appeal valid and obligates the Municipality of Santa Cruz to respond to the queries made. In its response, the local government argued that in the absence of milestones that demarcate where the 200 meters begin, a conclusion cannot be reached, and a topographical study will be necessary. To date, there have been no changes.

The role of the institutions in some cases reflects what happens at the community level. Therefore, it is important to address what is happening in the community.

Interference and restructuring of the communal fabric

This type of conflict cannot be understood without its social dimension. Communities with real estate pressure become a scenario where the intentions of real estate developers are not entirely clear. The private use of water for residential purposes and the illegal use of the ZMT are accompanied by campaigns, donations, and other gestures that seem to seek to divert attention from the grievances committed.

It would be unfair if it is not recognized that Allen and Marvez have some support in Marbella. These people usually have a working relationship or somehow a family member depends financially on them. There function is like that of the farm foreman, the one who is in charge of managing the territory of others. This is understandable if one takes into account that coastal communities suffer from difficult economic conditions. What needs to be emphasized is that this is vertical relationships governed by dependence and subordination to the interests of others. It can be said that it's to the interest of others because, in statements collected by the media, Allen affirmed that Marbella is owned by him. The more than a thousand hectares, the projects, and have had control of the water in Marbella for more than 10 years, attest to this statement.

Since 2016, when the press began to echo the irregularities in water management and the ZMT, Allen and Marvez began a community-wide self-promotion campaign. Local teenagers with new surfboards or playground donations by Marbella Group Developers started showing up in the community.

Marvez, for his part, went from an intransigent position that demanded water for his projects as a “human right”, to a more relaxed position in which he affirms that they have never refused to collaborate with AyA. This is striking since, according to neighbors, the supply of drinking water to the less than 200 families in Marbella was not a matter of discussion until large real estate developments arrived in the community.

But this is not enough, it is necessary to nullify any kind of dissent towards the aspirations of the real estate sector. For example, the NGO Marbella Verde was harassed until in an open meeting in the communal hall on December 9, 2019, the harassment turned into verbal attacks. The meeting was attended by officials from the Municipality of Santa Cruz and AyA. The objective was to ventilate and resolve the complaints filed in relation to water management and the ZMT.

Marbella. Image of Alba Sud.

Alba Sud, present at the meeting, was able to verify that the attacks came from the head of the ZMT office of the municipality (2), representatives of the real estate developers, and a group that was identified as construction workers. It is worth mentioning that the developers mentioned did not participate in the meeting.

What has Marbella lost in these years? First, Marbella has yielded huge portions of land for residential tourism use. The occupation of coastal residential areas does not have the local or even provincial population as their goal, but they are occupied by second residents, mainly from other countries. Second, because of Jeffrey Allen's administration, Marbella lost the ASADA. A community management space that has a central character in other coastal communities. It can be said that Marbella has ceded the management of its community to third parties.

What comes next?

The most recent chapter in this long conflict involves the inclusion of new actors. Together, the Costa Rican Federation for the Conservation of the Environment (FECON) and the Tempisque Conservation Area (ACT) has made public a statement in which it is made known to the general public that documentation has been presented to the Municipality of Santa Cruz, where it is requested to resolve the irregularities in the ZMT as soon as possible in accordance with the Costa Rican legal system. The requests filed by FECON are:

1) Cancel the Municipal Agreement approved without a technical-environmental basis in December 2019, which authorized the installation of electric lighting that would be affecting the reproduction cycle of turtles in this area, so that it is eliminated.

2) Investigate excesses in the use of construction permits granted to a bar-restaurant that has established illegal infrastructures usurping the ZMT.

3) Demolition of a wooden house within the ZMT, which was built in the area without having the environmental license as established by the Construction Law.

4) The demolition of a bridge built without an environmental license; work permits in the riverbed by the Water Directorate in Playa del Coco in Marbella.

5) In addition, information was requested from the ACT on a complaint about logging within the mangrove swamp of Playa del Coco, which was presented by the ACT itself, to add FECON as a complainant.

The participation of FECON and ACT is no accident. It responds to the need to seek support outside the communal borders. The dynamics of the tourist enclave model that Marbella follows restricts the possibilities of influencing the community through traditional mechanisms of cantonal participation. At the same time, it is a call for other organizations and people from other latitudes to find out what is happening in Marbella.

The private control of resources and public spaces is fundamental for the appropriation logic that residential tourism brings. Through various strategies, real estate developers have influenced the community violating the Costa Rican laws in the process. The conflict has also revealed the deficient institutional response in terms of protection and safeguarding of common goods, both the local government and decentralized institutions have done little to correct the grievances. The institutional void and the lack of proposals in Guanacaste that allow inclusive tourism development in coastal communities is once again evident. In Marbella, tourism activity is not debated, nor is the arrival of new residents objected. What is questioned is in what way real estate agencies and construction companies have come to take control of every aspect of community reality.