08-02-2021

Costa Rica: criminalization of the environmental movement and tourism conflict

Arturo Silva Lucas | Alba SudThe Costa Rican Federation for the Conservation of the Environment (FECON) publishes a report compilates by Mauricio Álvarez, Alicia Casa and Fabiola Pomareda on the criminalization of environmental defenders. The book allows us to reread the tourist conflict as a dimension of the environmental conflict.

On December 7, 2020, the Costa Rican Federation for the Conservation of the Environment (FECON) presented the book A memory that becomes a struggle: 30 years of criminalization of the environmental movement in Costa Rica. The publication is the result of the support of the Rosa Luxemburg-Mexico Foundation, the Heinrich Böll-El Salvador Foundation, the Research Center in Political Studies (CIEP) and the Socio-environmental Kiosks Program of the University of Costa Rica (UCR).

FECON is a Costa Rican platform with 30 years of experience that brings together more than fifteen organizations and that together develop actions in the field of environmental defense and social justice. Based on its own database, as well as other institutional sources, accompanied by various testimonies, the book constitutes an exercise in historical memory of the socio-environmental conflict in Costa Rica narrated by one of its leading organizations.

You can download the book by clicking here.

The book reviews 94 acts of violence against defenders of nature that have left their mark on the recent history of the socio-environmental movement. It is thus discovered that Costa Rica is not far from the cycles of criminalization and harassment of environmental defenders seen in other latitudes. But the information provided by the book also allows introducing the tourist conflict from a new perspective: in tourist territories, journalists, activists, public officials, community leaders are also targeted for their defense of nature.

Years of criminalization

Since 1970, the year in which FECON registered the first act of violence, conflicts over land and its resources have been part of the recent history of Costa Rica. Data collected by FECON in the State of the Nation Program shows that between 1994 and 2016 the number of collective actions for environmental issues has increased by 14%. For FECON, this conflict is the result of the deepening of neoliberal policies and has one of its main responsibilities in the government.

Throughout ten chapters, FECON shows how the Costa Rican State has been the main generator of disputes and conflicts. It went from a mediating role to promoting them, either by omission, inefficiency or lack of institutional frameworks that lead to a prompt solution in accordance with national and international legislation. One of the greatest contributions of the book is that it breaks with the myth of the activist as an isolated, radical individual, opposed to development and well-being. It shows that in most cases they are part of large community networks. Above all, because the cycles of criminalization have also affected park rangers, judges, municipal employees, and public officials.

Criminalization is defined here as "the process of actions and strategies carried out by state and private entities, which seek stigmatization, denigration, intimidation, delegitimization and demobilization of socio-environmental and territorial struggles" (Álvarez and Casas, 2020: 10). Criminalization is a strategy that is made up of a cycle of actions that do not always occur in a linear manner: disqualification-stigmatization, lawsuits, threats-harassment, attacks and, in the worst possible outcome, murder.

The 94 acts of violence that the book compiles are presented in the form of chronological lists grouped into six categories together with a brief description of the context, name of the people involved, year and judicial outcome. In total there are 18 class action lawsuits, 7 individual lawsuits, 10 arson, 21 threats, 25 attacks and 13 murders. The large number of cases that are unpunished or that remain open even though in some have passed more than thirty years stands out.

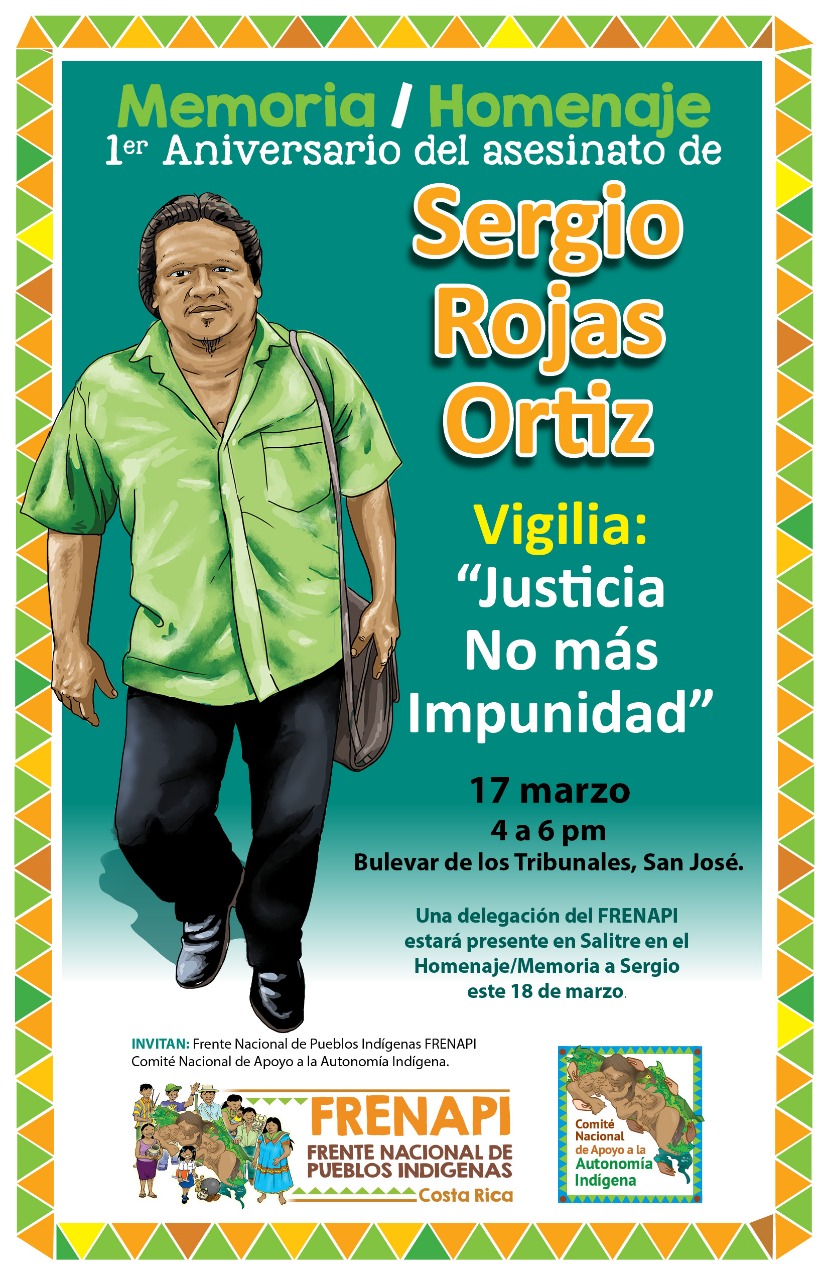

Another important contribution is that it makes visible the structural dimension of the events it reviews. This becomes clearer when the indigenous or peasant component is present. Land possession and use of the territory are key to explaining the unsolved murders of indigenous leaders Sergio Rojas in 2019 and Yehry Rivera in 2020 in the southern part of the country. Sergio and Yehry led movements for indigenous autonomy that, faced with institutional laziness in complying with legal agreements that guaranteed land tenure, carried out actions to recover land stolen by non-indigenous rancher groups.

On the other hand, it is also evident that women are also present in most of the exposed cases. Testimonies such as that of the activist Alicia Casas of the Costa Rican Social Ecology Association summarizes the risks of being a woman and a defender of nature, “as women it is important to highlight how repression, threats and persecution are different for women and how they come to represent a triple and fourth cross, which is carried only by the fact of being women” (Álvarez and Casas, 2020: 21). Apart from suffering the same cycle of criminalization as men, being a woman means that harassment contains a high degree of sexual content. Public and private discredit is sought, while traditional gender roles are reaffirmed. Another aspect that Alicia Casas points out is that of invisibility. Underestimated by public officials at first, when the mobilization reaches a certain incidence, "it is when male leaderships emerge that monopolize attention and can make women's leadership invisible on these struggles that they sustain" (Álvarez and Casas, 2020: 23).

FECON identifies that one of the triggers of conflicts is the lack of consultation or prior informed knowledge of the communities. Participatory processes that propose territorial development from the bottom up are lacking. Governments promote a development model that ends up being antagonistic to the aspirations of the communities. Thus, the gap between traditional uses of nature resources and the interests of the government and private investments is deepening. It is there where collective actions and networks in defense of the environment arise.

Most of the 94 acts of violence against nature defenders presented in the book have occurred outside the Greater Metropolitan Area. The further away from the urban center of the country, the more socio-environmental conflicts occur and, therefore, the higher the cost for defenders of nature. Many of these areas represent the borders of exclusion, an increasingly blurred border that separates the rural from the urban world.

Cases such as the murder of the Swede Olof Wessberg in 1975, responsible for the Cabo Blanco Reserve, stand out. Wessberg was killed in Corcovado while exploring the idea of turning it into a national park. Despite the killer's motivation to avoid Wessberg's intent, today Corcovado is a national park. In national parks it is common for park rangers to be the first line of defense against illegal hunting and logging. The text compiles many cases in which park rangers in different Protected Wild Areas (ASP) are confronted with firearms and knives, marauders and in some cases the trials end up proving the aggressors right.

In other cases, coastal destinations in which ASP coexist have resulted in persecution and criminalization. In the South Caribbean are located the Cahuita National Park of state-communal co-administration and the Gandoca-Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge. There, public complaints about the destruction of wetlands have been the subject of threats and defamation lawsuits against activists. In the worst case, they have suffered physical assaults as happened to Philippe Vangoidsenhoven at the hands of a municipal councilor in 2019.

The tourist conflict

Tourist territories are destinations that receive a significant number of people who carry out leisure and recreation activities. In addition, it is considered this way when these activities involve a break with the daily routine. It is common that when we talk about tourism it is associated with the concepts of free time and / or vacations. Leisure and recreation spaces are valued based on practices that are given a priori by social groups. These spaces are revalued based on the centrality of tourism. Once this happens, the tourism industry readjusts the territory to guarantee its operation and profitability. In this process, the State is a key actor when it comes to distributing the costs and benefits that tourism activity can generate, as well as the response to conflicts that may arise.

Source: Arturo Silva.

The relationship that the tourism industry establishes with the environment is significant for Costa Rica because it sustains its tourism offer on its natural and scenic wealth. According to the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT), the main places of visitation are the destinations of Sun and Beach and Protected Wild Areas (ASP). The Sun and Beach destinations concentrated 72% of visitation by non-resident tourists in the 2017-2019 period and the annual average of visitation in ASP for the same period was 2,155,071 people including resident and non-resident tourists (ICT, 2021). A relevant number if one considers that the national population is around five million inhabitants.

Because they are massive destinations with high commercial value, the development of large tourist infrastructure in coastal areas entails the destruction and / or dispossession of natural resources. In this scenario, it is common for defenders of the environment to emerge who point out the environmental cost of a tourism industry based on the principle of perpetual growth. On the other hand, ASPs are an intrinsic part of the Costa Rican tourist map, but they are not absent from actions that threaten the environment. The risk for defenders of the commons remains high despite having a legal framework that on paper protects and supports the conservation of these special territories.

Some relevant episodes

In Guanacaste, the incessant real estate tourism growth has led to a growing conflict over spaces and natural resources. The Sardinal conflict in 2007 stands out in the text. On that occasion, the community opposed the construction of an aqueduct that would bring water to coastal residential complexes. The community argued that the residential have contributed little to the provincial development despite being part of the "tourist plans." Apart from being repressed by the police on several occasions, residents and journalists covering the conflict received anonymous threats by electronic means. In a well-known strategy, community leaders were denounced for coercing the right of free-movement of public officials. After years of litigation, in June 2020, the court ruled that there was never full evidence to corroborate such a crime, so it remains in the file 17-001843-412-PE.

Source: Arturo Silva.

Even today, conflicts like that of Sardinal continue in Guanacaste. Currently, Marbella beach is a niche for new residential tourism investments that, over a precarious workforce, have threatened access to drinking water, destruction of mangroves and the appropriation of the Maritime-Terrestrial Zone by residential complexes. On January 8, the newspaper Semanario Universidad has attested to threats against neighbors who have opposed this type of tourism development.

In indigenous territories in the south of Costa Rica, tourism initiatives have emerged based on creating local development alternatives that counteract the historical abandonment of the State. Unfortunately, they occur in a context of structural violence that led to the assassinations of Sergio Rojas and Yehry Rivera. Angélica Picado Duarte published in Alba Sud a detailed review of several local projects in which self-management of the territory prevails, configured from other imaginary compatible with local production and traditional practices.

Justice and truth

Little can be added to the detailed analysis that the book undertakes. FECON demands the creation of a special jurisdiction that protects the integrity of the defenders of nature, as well as the creation of a Truth Commission that clarifies all crimes against environmentalists.

In Costa Rica, the tourism conflict is an extension of the environmental conflict. For a country that exports the image of being sustainable and friendly to the environment, texts like that of FECON reveal an uncomfortable reality to say the least. Above all, if one takes into account that its tourist brand is that of a country of peace and harmony with nature.