02-07-2021

Precarious futures for gender equality in the post-COVID tourism world

Carla Izcara | Alba SudLast Thursday, June 17th, a webinar on gender and labor precariousness in the tourism sector in the post-COVID19 context took place. The event was organized by the Transforming Tourism Initiative, a global network of NGOs, tourism professionals, and academics, of which Alba Sud is a member.

Photography by: ILO/Better Work Indonesia. Creative Commons license.

The event is part of a series of webinars that the Transforming Tourism Initiative is organizing about tourism and COVID-19. Andy Rutherford, founder of Fresh Eyes - People to People Travel, made a brief presentation of the network and explained that tourism must be understood and built from a local perspective with empathy and respect, seeking an equitable distribution of social and economic benefits.

After the opening, Stroma Cole, director of Equality in Tourism, took on the role of moderator and gave the floor to Angela Kalish, a member of Equality in Tourism. First, Kalish spoke about the volatility of the sector and explained how tourism has been one of the main drivers of privatization as it is inherently linked to the capitalist neoliberal economic system. Therefore, quoting Kalish, “the analysis of tourism transformation needs to happen in the context of changing the prevalent economic paradigm, which fuels tourism”. Secondly, she related the concept of precariousness to labor flexibility and pointed out that, in the case of tourism work, it leads to a lack of valorization, low wages, and hostile working hours, among other consequences. This precariousness of work affects women in particular, with greater incidence in the countries of the Global South as it interacts with other factors such as race, gender, and colonial stereotypes.

In addition, she presented some data regarding the impact of COVID-19 on women working in the tourism sector. First of all, there are approximately 120 million jobs at risk, especially in the Asia-Pacific region, apart from all those jobs within the informal economy that have disappeared in which their workers have been left helpless. This loss of employment has greatly affected women, just as the risk of contagion is higher among women because of their roles at work, such as in customer service or in cleaning; likewise, their domestic workload has even increased. To conclude her speech, she questioned the benefits of capitalism and proposed reevaluating neoliberal thinking against the sustainability of the planet and human development.

The second intervention was given by Ernest Cañada, coordinator of Alba Sud, who approached the concept of precariousness and its connection with the tourism sector and its interaction with gender inequalities. Precariousness is usually spoken of in terms of temporality, but this is insufficient as the reality is much more complex and that is why Cañada adopts multidimensional approaches to this phenomenon. Therefore, precariousness is a historical process resulting from two dynamics, one, as Kalish also pointed out, has to do with the processes of flexibilization of the labor force, imposed by companies in a context of globalization and global competition. The second one is due to neoliberal policies that have deregulated labor markets, weakened unions, and imposed legal frameworks that do not protect workers. This has resulted in the imposition of power relations that have ended up weakening the working classes.

In the specific case of the tourism sector, some consequences of this precariousness have to do with the structure of the activity. Some of these characteristics are the oscillation of demand over time, the possibility of doing a job with little training, and the strengthening of platform economies and financialization processes, accentuated since the global crisis of 2008. Taking into account the growing precariousness in the tourism sector and its high degree of feminization, Cañada wonders what the keys to this relationship are. Fundamentally, there is a process of naturalization of gender inequalities, and the tourism industry takes advantage of that by paying lower wages, offering part-time jobs, etc. Likewise, organizations such as the World Tourism Organization, instead of recognizing this as a sign of precariousness, defends the fact that thanks to these “job opportunities”, women can access salaried employment without neglecting their care responsibilities, that is, naturalizing gender inequalities.

Thirdly, Khawla Zainab, associate researcher at IT for Change, an NGO based in Bangalore, India, which works to ensure that technology contributes to human rights, social justice, and equity. In her talk, she presented the working conditions of women working as a freelance or as subcontracted employees in platforms from the beauty sector, which greatly resemble those of many women in the tourism industry.

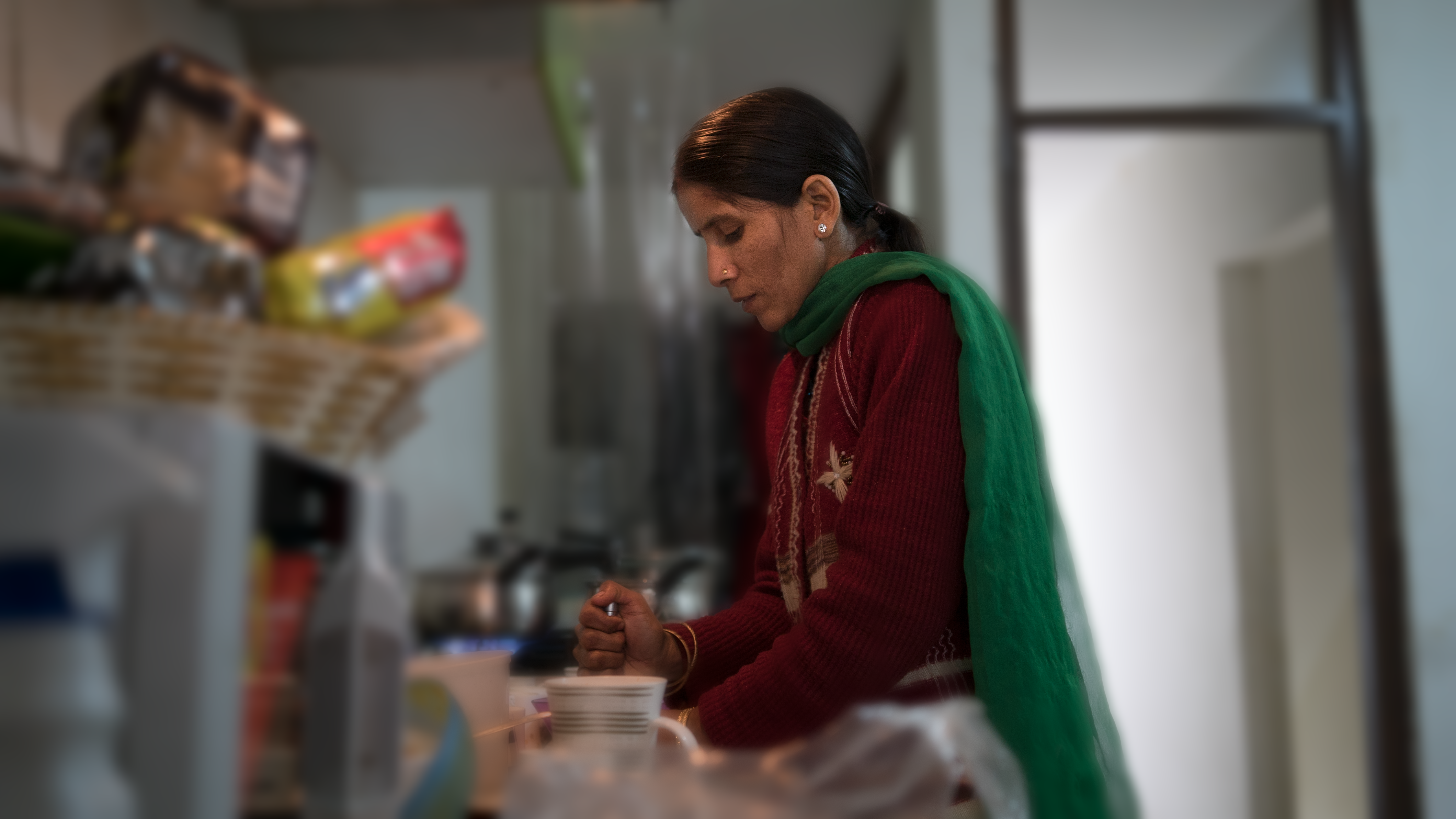

Laxmi Bhatt, migrant domestic worker. Photo credit: © ILO/J. Urmila 2018. Creative Commons license.

The first characteristic of employment in platform economies is the feminization and precarization of these jobs. Secondly, gender-based occupational segregation, pushing women into jobs that are perceived as an extension of domestic work, which is devalued and lacks visibility. Fourthly, she explained how platform economies tend to monopolize the sector due to their capacity for network expansion, including more and more players in their ecosystem and making survival difficult for small companies with less capacity for growth. Likewise, high commissions are a reflection of the extractive tendencies of platforms. Finally, their human resources management is based on unknown algorithms, for instance, workers do not know why they are assigned more or fewer tasks and so, the relationship between the company and its employees is opaque.

As the previous speakers had already pointed out in their speeches, since the financial crisis of 2008, there has been an exponential growth of platform economies. Although these forms of business are a result of technological advances, they generate traditional forms of work and reproduce the same dynamics of precariousness. In addition, the commission model tends to exacerbate this precariousness. Khawala Zainab presented the results of her study based on the Urban Company, in which she highlights, on one hand, the abusive commissions that these companies ask their workers and, on the other hand, the increase in instability and lack of labor protection caused by the pandemic. Moreover, these workers are perceived as easily replaceable, a fact that influences this instability. The speaker concluded by explaining how COVID-19 caused a migration crisis in India in March 2020 that affected women in particular.

The last speaking turn was for, Baiq Sri Mulya, founder of SembaluNina, a women's organization based in Indonesia dedicated to increasing leadership opportunities for women. She offered a more positive view of the post-pandemic context and described it as an opportunity to transform the mismanagement of tourism towards a more sustainable development driven by women and based on scientific evidence. The initiative was born out of their concern about the lack of water, disrespectful behavior by tourists, and poor waste management. There are currently 34 women involved in the initiative, but they are trying to enlarge the group and reach more leadership positions in local development. In order to achieve this goal, they believe that the Sembalun area, made up of six villages, needs to work as a single ecosystem to address the problems generated by this activity.

Picture by SembaluNina

To finish, she pointed out that their main challenge is to break the silence imposed on women and to participate in the decision-making processes, spaces traditionally occupied by men. Moreover, she believes that on several occasions their opinion is still not taken into account simply because they are women and, as a result of that, they have to be much more persistent. On the other hand, she insisted on the necessity of strengthening trust between NGOs third sector and the government, since these entities have traditionally been stigmatized for cases of corruption or criticism of the government.

In the end, they concluded that each context is unique, but there are mechanisms to try to reverse these situations. Cañada proposed strengthening the organizational capacity of women workers to defend their rights in each context, either through union structures or renewed forms of collective organization. At a second level, changes would have to be introduced at a local, national and international legislative level to generate greater protection. Stroma Cole summed it up in three words: legislation, unionization, and more power to working people.