06-12-2020

Life and Pain of life in Holiday Regions: Mental Health and the Development of Tourism in Quintana Roo, Mexico

Sébastien Fleuret & Clément Marie dit ChirotFirst destination for tourism in Mexico, the state of Quintana Roo also shows itself to face acute issues in mental health. In the face of health system shortfalls, the civil society organizes itself to tackle this phenomenon which could be worsened by the current sanitary crisis.

Photography by: Alba Sud Archive.

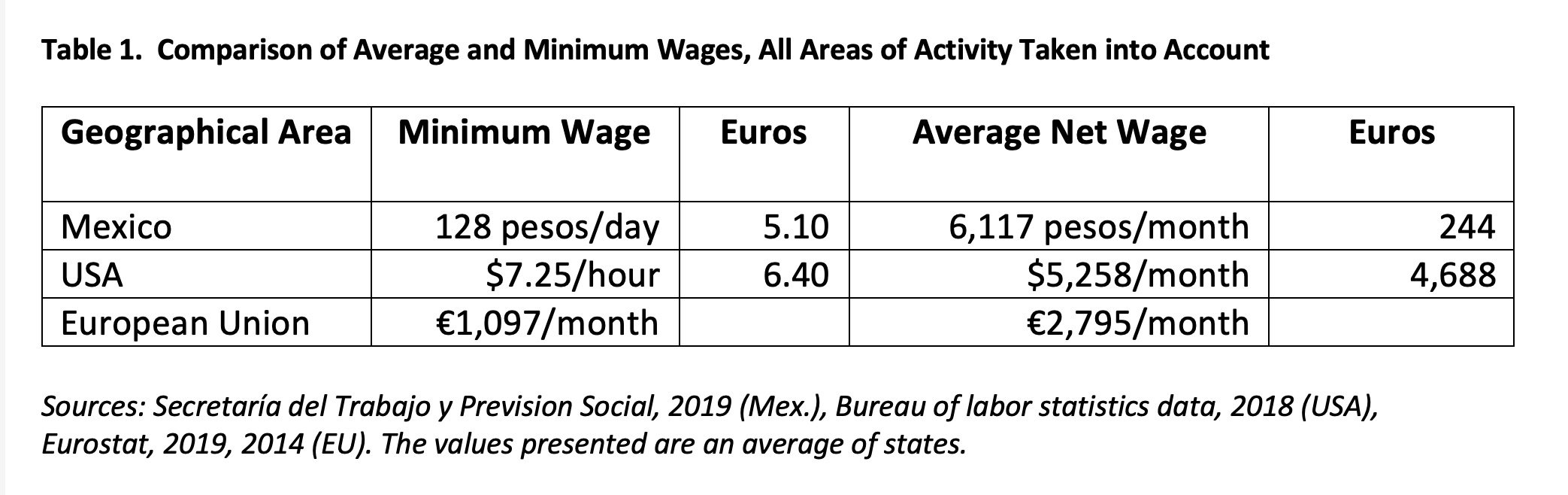

International tourism brings together in one place a hedonistic population that has come to relax for a holiday and the local population, which in most cases is mainly destined to work in the tourist sector and serve the first population. There is often a major – even a huge – difference in living standards between the first and second populations (tab. 1). Nevertheless, tourists may on the face of it legitimately travel with a peaceful conscience, believing that they contribute to the economic development of the region they are visiting.

Nevertheless, this development is questionable, especially with regard to one indicator: health. There are significant and regularly neglected occupational health issues in the tourism professions: chronic fatigue and muscloskeletal disorders are legion and rarely treated (Cañada, 2015). We may cite the example of a beach waiter in Tulum on the Riviera Maya, who told us that he works 12-hour or more days for 6 days a week, without real holiday periods. He was visibly exhausted and the fact of having to pace up and down the sand all day had caused severe muscle pain in his legs. All this is done for a daily wage of 300 pesos (approximately 15 euros), supplemented by a few tips when everything goes well.

Although his health insurance reimburses basic healthcare, occupational health is out of the question in the Mexican system. But it is probably in the mental health sector that the problems are the most glaring, in a context of almost total lack of responses from an impoverished healthcare system.

The reflection developed in the following paper is based on the initial results of exploratory research conducted in the Riviera Maya in January 2020. During this research, comprehensive interviews were conducted with healthcare professionals and patients [1]. Although at this stage, we do not intend to make definitive conclusions on this topic, the survey nevertheless enables us to consider a few lines of explanation, which are serving as a basis for more detailed work currently in progress.

The Extent of Mental Health Issues in Quintana Roo

Although Quintana Roo enjoys an international reputation for its fine sandy beaches and seaside resorts popular with tourists, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) this south-east Mexican state also stands out for having one of the highest suicide rates in the country. In 2017, this suicide rate was 8.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, placing Quintana Roo in fifth position among Mexico's thirty-two states [2]. This is far higher than the national average, which for the same year was 5.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants (INEGI, 2019a). In a sign of the scale of mental health issues in Mexico's main tourist destination, Quintana Roo has recorded similar trends for other pathologies. For example, anxiety disorders (which reportedly affect 14% of the working population compared to 7% at national level) and alcoholism (Reséndiz Escobar et al., 2018). Such an observation may seem paradoxical given the region's economic vitality and strong appeal, especially in the north of the state where the tourist towns of Cancun, Playa del Carmen and Tulum are located. This vitality is reflected in a significant phenomenon of internal migration linked to the influx of workers from Mexico's other states. They are attracted by the job prospects that the development of tourism provides (Varela Llamas, et al., 2017; García de Fuentes et al., 2019). How then is this particularity to be understood? Over the past few years, the public authorities and local civil society have become aware of the phenomenon. For a long time, however, the issue seemed unthinkable, if not taboo, as an article published in the national daily La Jornada in 2006 reminds us. Although a growing number of suicides was observed in Quintana Roo during the early 2000s, the health authorities questioned about it at the time cited the Yucatan Peninsula's tropical climate and high temperatures – inhibiting dopamine secretion – as factors aggravating the risk of depression and suicidal phases. Although mental health is inevitably determined by many factors, and although the physiological dimension certainly needs to be taken into account, other social and environmental factors could nevertheless help explain this situation, which now requires urgent management by the authorities. The intensity of the phenomenon seems exacerbated by the specific features of Mexico's leading tourist destination: considerable migration of workers, working conditions, growing insecurity, and the precariousness of the local health system. The problem could also be exacerbated by the crisis the region has experienced since the start of the COVID-19 epidemic.

Migrating to Quintana Roo: Between Future Dreams and Psychosocial Risks

The migratory appeal of Quintana Roo is one of the major consequences of the region's economic development, generated by the expansion of tourism. This particularity is seen in the state's demographic structure. In 2010, 53% of its resident population stated that they had been born in another region of Mexico, especially in other south-east Mexican states such as Yucatan, Tabasco, Campeche and Chiapas (Garcia de Fuentes et al., op. cit.). Moreover, this share, which is over 60% in the state's main tourist towns, places Quintana Roo among the main states receiving internal migration in Mexico (Luna Garcia, 2019). It is evidence of the massive influx of migrant workers looking for job opportunities in the tourism-related construction and services sector. Although a sign of the region's economic vitality, Quintana Roo's migratory appeal is nevertheless a risk factor for migrant populations' mental health. Many researchers have demonstrated that these populations are more exposed to certain forms of mental suffering, including within the context of internal migration in the same country (Luna Garcia, 2019; Cardano et al., 2018).

In Tulum, the road leading to the hotels by the beach ironically starts with this sign. Photo credit S. Fleuret.

Being uprooted, solitude and difficulties adapting to the local society are all sources of unhappiness, as evidenced by a young women aged about thirty who works in the hotel industry. She experienced severe depression for a few years after settling in Playa del Carmen: "We have an expression here that says there are two possibilities with this town: either it adopts you or aborts you!" Emphasizing that hotel work absorbs so much time, her personal account describes a social life almost exclusively limited to professional relationships, which are themselves unstable due to the high turnover in the hotel industry. This instability even affects private life when the instability of career paths entails frequent changes of flatmates and even of lodgings. Although, faced with the lack of satisfactory job prospects in her home town, she recognizes that her economic situation has improved since arriving in Playa del Carmen, she cites the example of many friends whose feeling of isolation has driven them to return to their own region: "Many people grow weary of being alone and end up going back". In other cases, such as a young 18-year-old man from Chiapas who is a maintenance worker in one of Riviera Maya's hotels explained, it is not so much the distance from friends and family that is at stake, but rather the burden of expectations weighing down migrant workers when they have to provide for the needs of their family, who have remained in their home region. He comes from a poor family and is the eldest son in a large group of siblings. He sends most of his earnings to his family and mentioned several times his psychological distress in the face of a responsibility that he struggles to assume. Constrained by this burden that is too onerous for a young man barely out of his teens, he explained that he has several times considered ending his life.

The Effects of Tourism Work on Mental Health

Quintana Roo's economy is to a great extent focused on tourism, which accounts for 70% of the state's GDP (Brown, 2013). As a result, its labour market, marked by the predominance of the hotel and construction sectors, has specific features. According to Cheroky Mena Covarrubias, a psychologist and coordinator of Dile psí a la vida, a civil association for suicide prevention for whom these two business sectors are focos rojos for workers' mental health, especially with regard to suicide, this economic hyper-specialization acts as an additional risk factor. "It's a very competitive working environment, characterized by excessive hours and workload. In the best case scenario, people have one day off a week, with working days varying between 8 and 12 hours. What sort of life can you hope for in these conditions? People don't even have time to wash their clothes and look after their children, let alone have time for themselves." A female hotel employee we met in Tulum explained that she works from dawn to dusk 6 days out of 7. Due to traffic problems, it can take her up to an hour each way to go to work and return home. When she gets home, all she wants to do is have a bath and sleep. She is not hungry, and either does not eat or else nibbles nanchos or some other junk food. When she has day off, she sleeps and does not do anything else. What about leisure activities? To be honest, she has not even thought about it. She would really like to change job and develop but even thinking about what she could do seems insurmountable since her mind is far too preoccupied for that.

The particularities of service and hospitality jobs in the hotel sector add to the workload, as a woman who had suffered from depression explained: "The hotel business is very demanding work, especially the jobs with guest contact. You're not allowed to feel bad and the face you show to guests always has to be the same, whether or not you're feeling well. You have to act a part in some sense." This phenomenon, called 'emotional labour' by the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild (1983), is expressed by greater vulnerability to psychosocial risks such as burn out, or by adopting additive behaviour. In this way, the new official mexican norm NOM-035 on the “occupational psychological risk factors” recently promulgated by the Secretaría del Trabajo y Previsión social, represents a significant progress toward more prevention of such risks. However, the implementation of this norm is recent (2020) therefore it is too early to estimate if it represents a significant progress for the employees of the tourism industry.

Photo credit S. Fleuret.

The mental suffering caused by working conditions and environment also has a knock-on effect on family. A psychologist told us that parents' unhappiness rebounds on teenagers whose parents are largely unavailable since their time is taken up by low-paid, insecure jobs (cleaning, service agents, waiters). She mentioned many attempted suicides (difficult to quantify and record) and cases of self-harm.

Aquí existe el miedo: Insecurity as an Aggravating Factor

Several healthcare professionals interviewed also emphasized the consequences on mental health of Quintana Roo's growing insecurity. Since 2016, the state has experienced a significant increase in levels of violence, expressed by a large rise in the number of murders: 145 in 2015 compared to 839 in 2018 (INEGI, 2019b). Although this increase is largely explained by rivalries and settling of scores linked to organized crime, Riviera Maya's main tourist resorts have also seen emerge new types of violence due to extortion (derecho de piso), which has affected many shopkeepers (Fuentes, 2017; Vázquez, 2019).

Under protection of anonymity, a psychologist working in Riviera Maya highlighted during an interview the extent of this widespread threat, and the psychological distress it is causing a growing number of patients. For some time, she has observed a specific problem among small business owners. "Everyone is affected, even people selling tacos and tamales. Many of them are forced to give up their business since they receive threats," she explained, citing the recent example of a tacos-seller who received gunshot wounds for refusing to pay the derecho de piso. For around the past three years, these testimonies are, in her opinion, a frequent reason for medical consultations "out of desperation". Whether real or perceived, the phenomenon is now something that many self-employed workers now have to cope with, especially in the tourism sector, for whom this threat has become a source of stress and anxiety. According to this psychologist, the people affected feel all the more helpless since it is often impossible for them to talk about it openly for fear of reprisals: "They can't talk about it to anyone; people are forced to remain silent." Faced with the lack of any possible response to this situation, this healthcare professional's own feeling of helplessness is palpable.

Community Responses to the Shortcomings of the Public Mental Health System

These various aspects show a local combination of factors conducive to the development of particularly acute mental health problems in Quintana Roo's tourist destinations. The situation is all the more worrying given that Mexico's main tourist region suffers from a glaring shortage of mental healthcare. With a population of more than 1.5 million inhabitants in 2015, Quintana Roo is in fact a poor relation in Mexico's mental health system since it is among the 7 out of 32 states without any psychiatric hospitals. The situation is also critical regarding the number of psychiatrists: the state only had 19 in 2016, i.e. a rate of 1.27 per 100,000 inhabitants. In same year, the national average was 3.68 per 100,000 inhabitants (Heinze et al., 2016) [3]. In Playa del Carmen, a city of over 200,000 inhabitants where part of the survey was carried out, only four psychologists are registered according to the psychologist Cheroky Mena. He described the extreme difficulty in accessing treatment for people suffering from psychiatric disorders in this holiday resort. This is over and above the prohibitive cost of a medical consultation in the private sector for a large section of the population. During the interview, he explained that patients requiring urgent admission to hospital have to be redirected either to the city of Mérida, the capital of the neighbouring state of Yucatan, which is almost four hours' drive away or to the psychiatric state hospital in the city of Campeche (more than five hours’ drive away). These difficulties in accessing treatment appear in the personal account of a woman aged about forty with bipolar disorders. Having been diagnosed a few years before settling in Riviera Maya, she described the huge contrast between the range of treatment she received in Mexico and what exists in Riviera Maya: "When I lived in Mexico, I could rush to the National Institute for Psychiatry, which is a public hospital, whenever I had a crisis or suicidal thoughts. They could even admit me to hospital if the doctors thought it necessary. Here no, there's nowhere to go and no emergency service!"

Over the past few years, the issue has worked its way into local public debate. For example, in 2018, when Laura Beristain, the current president of the municipality of Solidaridad, promised during the election campaign leading up to the municipal elections to establish a mental health centre in Playa del Carmen if she won the election [4]. More recently, the issue has been put on the state-level political agenda, with the introduction of a mental health bill for Quintana Roo. A series of initiatives backed by civil society has also recently emerged to compensate for the shortcomings of the public health system. This is notably the case in Playa del Carmen, where the association for suicide prevention "Dile Psí a la vida", has played its part since 2016. Backed by a group of healthcare professionals, the association is based on a "project for social psychology and community intervention, according to a principle of participatory action research." During the past years, a local network for the prevention of suicide has been jointly driven by the association and the authorities of Solidaridad, the municipality of Playa del Carmen [5]. For example, one action implemented has led to setting up emergency hotline support for people in psychological distress. In addition, self-help groups have been established, where people in distress can meet each other or with healthcare professionals and discuss their difficulties. These group workshops also involve new forms of financial solidarity to deal with emergency situations. As Cheroky Mena explained: "Attending group sessions costs 50 pesos per person (less than three euros, i.e. ten times cheaper than the cost of a private consultation). The money is pooled and if someone in the group is in difficulty, we dip into this common fund to help them," he explained, citing the example of a person who received 1,000 pesos in this way to purchase drug treatment. "Since the person couldn't buy the right treatment in Playa del Carmen, they had to get their family to purchase it in their home town, and then to post it to them", he explained.

The question of access to drug treatment is another issue revealing the precariousness of the local healthcare service, and of the gap that remains to be bridged to curb a phenomenon that researchers, stakeholders in the health system and in tourism have barely begun to study.

The question of access to drug treatment is another issue revealing the precariousness of the local healthcare service, and of the gap that remains to be bridged to curb a phenomenon that researchers, stakeholders in the health system and in tourism have barely begun to study.

More Articles

-

5º Seminario Perspectivas críticas sobre el trabajo en el turismo

General News | 25-03-2025 -

Turismo comunitario urbano en Brasil: una pedagogía de la resistencia

General News | 25-03-2025 -

De los Alpes a los Andes: esquí y cambio climático

General News | 20-03-2025 -

Tras los disfraces: el trabajo de las costureras del Carnaval de Brasil

General News | 18-03-2025 -

Ciudades turísticas: evolución y perspectivas de un modelo fordista de producción turística

General News | 13-03-2025