19-02-2021

Touristocracy: organized vulnerability

Joaquín Valdivielso & Jaume Adrover | TerraferidaThe covid-19 pandemic has been an illuminating event in tourism societies. In a context of paralysis, it has served to make explicit distinctive features of what could be termed touristocracy. The Balearic islands is a paradigmatic case study.

The stand-by that the COVID-19 pandemic has meant in 2020 recalls the image of the state of nature. This hypothetical devise allowed classical thinkers to represent a kind of original stage in history, a suspension of the “normality” of institutions, in which we could see more clearly under which prerequisites one would be willing to subject himself or herself to the social contract, and in which not. Focusing on the Ancien Régime, then no one would submit to the arbitrary power of a despotic regime -they believed- but only to the law agreed by free and equal subjects, more or less what we would call nowadays a democracy. It is not by chance that the pandemic has been seen as a “total social fact”, “inaugural experience”, moment for a “new social contract”, a “reconstruction deal”.

Empty streets, parks and squares, beaches and airports, are samples of this suspensive moment of the social deal. This is the purpose, for example, of the collaborative project “Closed for holidays. Portrait of a tourist void”, by José Antonio Mansilla and Sergi Yanes, which collects pictures of various tourism destinations, usually flooded by visitors, now deserted. Thus, we can see “tourism spaces, not as unproductive spheres” but open to alternative forms of social production. An exceptional spot of a tourism society in reset, in a state of nature, is the Balearic Islands. It is an extreme case of a tourist region in Europe: until 2020, tourism represented 45% of GDP, 28.7% of employment, with a ratio of 16 tourists for each resident.

In June 2020, after months of locked airspace and under official state of alarm still in force, first tourists, exempt from covid tests or sanitary quarantine, arrived in Palma. The magazine Diagnóstico Cultura wondered whether this was not a prove of a “touristocracy”. Surprisingly, this term has no tradition in tourism studies, and it has barely been used in the media (as it is the case for touristcracy and touristocracy). Few places are as conducive as the Balearic Islands to test what a touristocracy may look like and whether the pandemic has triggered a disclosing effect of the social deal underlying a tourism society.

The touristocratic regime

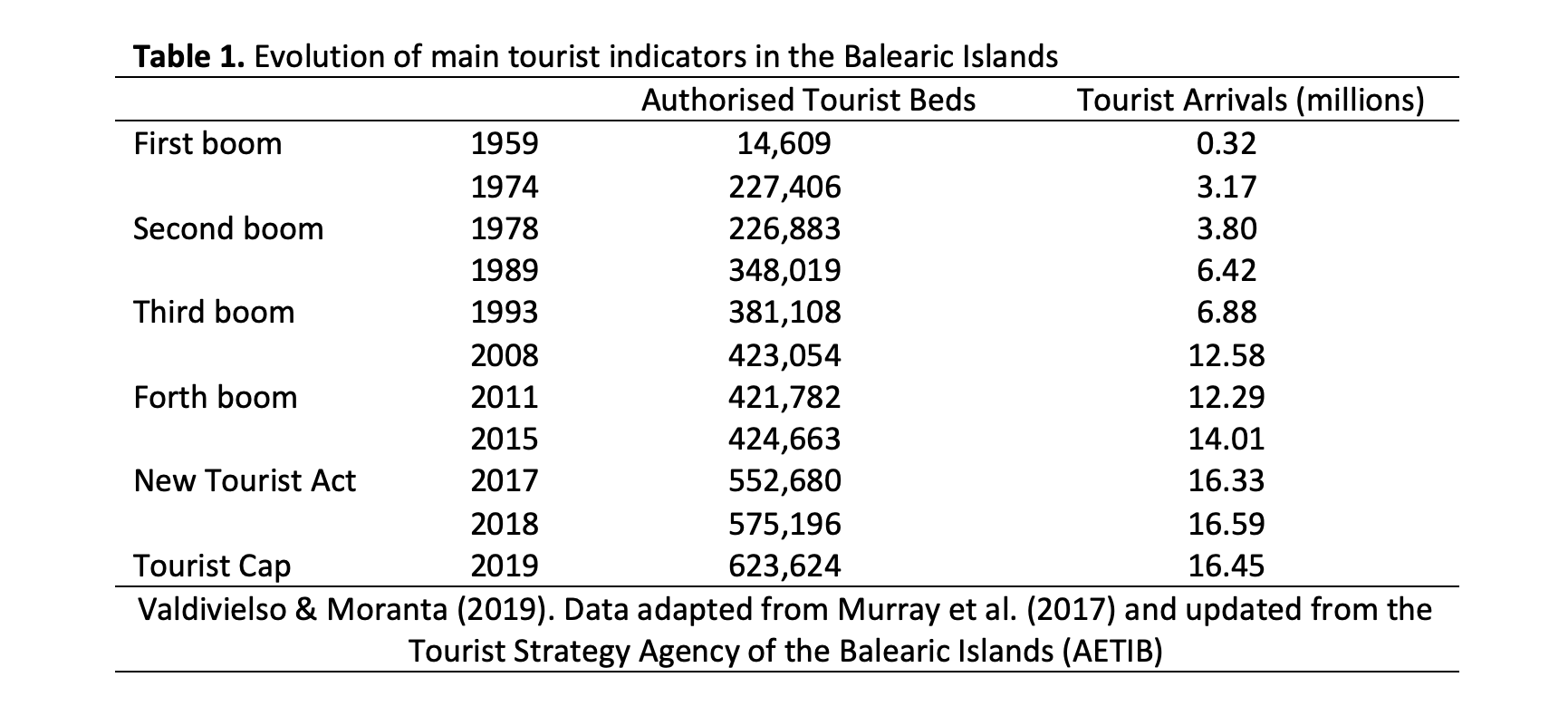

The already spasmodic behaviour of Spanish tourism economy is heightened in the Balearic case. Spasms, “booms”, have followed one another like a cycle, with ups and downs, whereas the spread of the tourism frontier, amalgamated with the real estate business, has been colonizing diverse spatial niches. In the last of the booms, the archipelago reached one of the most intense airbnbfications worldwide. The cycled sequence has been also accompanied by alerts about negative environmental and social effects of overtourism, danger of oversupply, and vulnerability caused by what is popularly said “putting all your eggs in one basket”. As a result, different regulations have been enacted in the frame of a never-ending dispute about the “tourism model”. As shown in table 1, at a decisive moment (until 2017) a kind of social deal was settled around tourism containment, and the pool of authorised tourist beds kept almost frozen. For two decades, all the presidents of the regional Govern, conservative or progressive, have publicly defended the need to diversify the economic model. However, as official figures show, the number of tourists has steadily grown.

The heated controversy around holiday rental is not accidental. Balearic Islands beat all negative records in access to housing, rising prices, with 4.98% of the total housing stock being employed by tourist use, which reaches 20% and 30% in some municipalities. As a whole, it multiplies by 5 the pressure in, for instance, the province of Barcelona. To the effects on the residential housing market, we must add those typical of urban gentrification processes, but also those of rural gentrification and environmental impacts related to rurban tourist use -in water or energy consumption, tertiarisation of rustic land, and so on. In addition, topics about the sharing economy have been refuted in the Balearics, thanks to data provided by various neighbourhood and environmental organizations, which have shown massive fraud, uberized labour, and concentration of supply (a single local super-host managed near 900 homes just in Airbnb, and Homeaway rented about 24,000). A new business stratum linked to the tourism exploitation of houses added to what has been described as “hotel aristocracy”. Altogether with their peers in other links in the tourism value chain -tour operators, builders, airlines, etc.- they compose a local, yet national and transnational integrated, tourism-real estate oligarchy.

COVID shakes the regime

As it is a common place in states of crises, the arrival of the COVID in February has been a disclosing moment for some of the features of the tourism regime. From the very beginning, the strain between movements to prioritize public health and those to prioritize the tourism business became clear; and the tension within the oligarchy itself between those with a maximalist stance to reduce risks and those with a minimalist position to deny them. Once the air and maritime space were closed and lockdown imposed, the economy paralyzed, various strata of the tourism regime mobilized in a front for the new normality. They had three challenges ahead: to obtain new regulatory measures and direct subsidies from the authorities; to isolate tourism from COVID, both in the sense of minimizing the risk of a contagion that could spoil the destination brand, and in the sense of denying that tourism was a vector of transmission; and to achieve direct management as a region towards international tourism issuing markets, and a comparative advantage as a “safe destination”.

Pressure to relax and suspend urban, tourism, fiscal, labour and environmental regulations was immediate. It did not acknowledge those sectors that maintained the tourism society while in reset -health, social services, agriculture and local industry, education, etc.-, where the Balearic islands are at the bottom in national rankings as a consequence of the tourism-real estate monoculture (i.e., it is the Spanish region with the lowest rate of primary care physicians). On the contrary, spurred by a group of conservative mayors, the oligarchy (construction companies, hoteliers, small and medium-sized companies, holiday rentals, travel agencieslobbies...) united against the regulatory framework, advocating for traveling subsidies, suspending the tourist tax, and cross-deregulation to start a rapid recovery through the same recipe used in past cyclical crises: cement and tourism.

Furthermore, “back to normality” became itself a discursive device, a narrative, with practical but no less symbolic effects. To typical official promotional campaigns and mottos such as “You cannot travel, but you can dream”, #SeeYouSoonMallorca or StayHomeMallorca, the explicit message of “We do not have a systemic crisis; it is a stoppage of the productive sectors that requires action from governments” was added. Among the practical effects, the aim was to put pressure for tourist rescue plans at the regional, national and European levels. No less it aimed at winning the narrative of expectations: the oligarchy publicly censured anyone who seemed slightly sceptical about the salvation of the 2020 tourist season, and did not hesitate to charge against European authorities, ministers, and the Spanish Prime Minister. All was about denying the reality principle, and keeping alive the dream of normality, at any cost.

Faced with pressures from a large spectrum of stakeholders to call an emergency round table, the regional executive split into two parallel movements: while, on the one hand, a Regional Reactivation Plan with elements of a “green agenda” was presented in open meetings; Tourism counsellor met behind closed doors with the regime’s oligarchy, including international agents such as TUI, and cooked a Decree of urgent measures (Law 8/2020) that was immediately approved. At the wake of some other Autonomous Communitiesunder conservative governments, although far from the extremes of Andalusia and Madrid, it entailed a huge regulatory relaxation, including the possibility of expanding tourist establishments, or building without a license, among other measures. To make up for this strategy focused on construction and promoted with delusional predictions, the executive was forced to approve a Decree (9/2020) of territorial protection, also sold with unrealistic figures, as it was then denounced by the environmental NGO Terraferida. While the islands insisted on the recipes of the past -cement and tourism-, cities like Amsterdam or Milan announced ambitious ecological transition projects.

Once the lockdown was lifted, a promotional campaign through a pilot plan for “safe air corridors” was launched in June. The oligarchy searched support from European lobbies in countries like Germany, which were at first little responsive to regain mobility with a country like Spain -in a far worse health situation-. Pressure of a group of German businessmen and residents in Mallorca, well received by the Spanish Minister of Transport, also helped. And thus, tourist activity gradually recovered, marked by images of tourists, airlines, and airports skipping health measures, that were already more lax than in neighbouring countries. So, contagion figures increased rapidly with the return to activity, what was the beginning of a second wave of the pandemic. Then, the tourism sector declared itself exempted from all responsibility, even when authorities responsible to manage the pandemic pointed to the lack of control at airports, and the need to quarantine tourists. When half of Europe began to impose restrictions on passengers from Spain, and tour operators such as TUI suspended bookings, the strategy to impose the narrative and deny reality was radicalized, to the point that the tourism lobby called for the immediate resignation of Fernando Simón, coordinator of the national health strategy, for having celebrated the restrictions on mobility in the United Kingdom or Belgium, where the incidence of the virus was much higher than in Spain, including the Balearic Islands. The oligarchy repressed any message stating that tourism could be a risk for public health. Primum turistae, deinde publica salutem.

The future of the touristocratic regime

If in the first wave the Balearic Islands could exhibit moderate figures of covid incidence, in the second the infection rates were the highest in the country, mainly in Les Pitiüses -Formentera and Ibiza. Whilst an indisputable lack of control at the airports, the entire archipelago became a “red zone” for European authorities. Therefore, tourist season was ruined. As a result, provisional data point to a drop close to 90% in main tourism indicators (number of visitors, tourist-led income, etc.); a collapse in annual regional GDP of -31%, being the Spanish region with the highest fall (it triples the country’s average of -11%), and, probably in the EU; and half of the workforce faced to subsidised layoff or unemployment. So, all hopes were focused on vaccination. Voices soon raised in favour of vaccinating workers in the tourism sector as a priority. Just in case, AENA took advantage of that moment to start a covert expansion of Palma airport capacity, that prompted the symbolic rejection of the Balearic Parliament.

Various experts in tourism studies, such as Mansilla and Tolo Deyà, have been warning that we are on the verge of a process of restructuring and concentration of the tourism business, from complementary supply to hotel chains, as a result of the pandemic. The lack of liquidity not only suffocates family businesses, but, as Ismael Yrigoy (2020) has shown in his study on Meliá company, the hotel oligarchy is also integrated into a complex transnational corporate and financial network, and now they face a window of opportunity for fat cats. Transactions of tourism assets have exploded in les Illes, where opportunistic funds such as Blackstone have already landed. In this context, the Govern has hired the accounting corporation KPMG, with its extensive record in corruption, to coordinate the rescue strategy for the local tourism sector thanks to the European Recovery Fund. Balearics’ hotel companies (Riusa, Meliá Hotels, Barceló Hotels, etc.), which doubled their profits in the background of the overtourism boom, and over-all a tireless oligarchy when it comes to opposing taxes take advantage of the “private profit, public debt” principle (it must be remembered that tax pressure in Spain, 35%, is up to 11 points lower than that of a neighbouring and also tourist country like France).

In this context, the debate on economic diversification and the change of model has reopened, though its echoes can hardly compete with the mantra of recovery and the new normality. Even very influential economists, such as Antoni Riera and Carles Manera, have suggested reducing the number of tourists and / or tourist beds, yet without abandoning continuous growth (in value, in wealth, but not in volume). The degrowth talk continues to be denigrated and associated with tourismphobia in the prevailing discourse, after having been the key in the debate on overtourism and de-touristization. Prominent political and social actors who now lament the costs of tourism monoculture had celebrated few years ago the Airbnb-led growth and the massive regularization of short term rentals explained above. Even now, during the first year of the pandemic (2021), the Consell of Mallorca has continued to allocate new tourism licenses for a hundred establishments –as it has being denounced by Terraferida -; Palma city council continues to give licenses for new accommodations –as it has being denounced by the Federation of Neighbours-; and hotel companies announce, as if nothing happened, that they will enter the holiday rental business niche. Actually, during the pandemic, demand for isolated second homes and traffic of private jets have skyrocketed in the Balearic. The transition from “over-tourism to non-tourism” does not allow for future predictions, as Pau Obrador (2020) says, but signals point to a new bubble tourism niche, exclusive also from the health point of view, which the Government of the Canary Islands is already campaigning for. These events are not accidental, as none of the emergency regulations enacted in this period considered measures to attack the causes of tourism-real estate dependency.

Touristocracy: the social deal for vulnerability

The fact that this pandemic crisis is in its origin an ecological crisis -the viral zoonosis originates in the loss of ecosystems and biodiversity- and that global hyper-connectivity has accelerated its transmission, makes economy an obvious co-responsible not only of causing but also of spreading the virus. From a degrowth perspective -that one warning for decades that either it is done voluntarily, orderly and fairly, or it will be in any case a forced, abrupt and chaotic degrowth- this crisis shows what happens to a growth society without growth, and anticipates what will happen on a larger scale caused by climate change. In this crossroads, governments suffer of cognitive dissonance: while they design ecological transition plans, they rescue carboniferous sectors, from oil companies to airlines. Tourism is one of them. And the Balearic insular, Mediterranean geography makes it almost totally dependent on global air mobility, and at the same time especially vulnerable to global warming.

Ismael Yebra (2018) has defined turismocracia as a “totalitarian and dictatorial way of governing” in which tourism interests prevail over rights. In the case of the Balearic Islands, it is confirmed that under a touristocracy not everyone enjoys the same rights. Touristocratic oligarchy is “more equal than others”, and they show it off. Touristocracy requires also coercion, included a functional integration that acts as a spider’s web from which it does not seem possible to get out without huge social costs; but not less, as Margaret Thatcher said, it requires “to change the soul”: it has to be agreed and loved, it presupposes the faith of the believer. However, as we have seen, there are also democratic counterbalance mechanisms, more or less effective depending on the case. In addition, there are many subjects at different scales, not only governments, making decisions, and they experience tensions, contradictions, splits.

The instance of the Balearic Islands under the COVID illustrates this typical schizophrenia of a tourism society. The sociologist Ulrich Beck (1998 [1988]) coined the expression “organized irresponsibility” to refer to the immanent contradiction of a system that generates dangers that cannot be attacked because no one can be accused or held responsible. In a tourism society, this danger is one of an extreme and growing vulnerability, but those who are primarily responsible can be identified. Whether mass tourism has died, or the post-pandemic transition lasts for years, or a “new normality” is reached, it is not wise to plan the future on almost total dependence on a single economic sector upheld on global hypermobility. The lesson taught by the pandemic reset is that touristocracy is the Old Regime and that the 21st century demands a new social deal.

More Articles

-

5º Seminario Perspectivas críticas sobre el trabajo en el turismo

General News | 25-03-2025 -

De los Alpes a los Andes: esquí y cambio climático

General News | 20-03-2025 -

Tras los disfraces: el trabajo de las costureras del Carnaval de Brasil

General News | 18-03-2025 -

Ciudades turísticas: evolución y perspectivas de un modelo fordista de producción turística

General News | 13-03-2025 -

Efectos del cambio climático en el turismo

General News | 11-03-2025