01-08-2024

Work and harassment in kitchens of community guesthouses in the brazilian amazon

Mayra Laborda & Cecília Ulisses Frade dos Reis | Alba SudSexual harassment against female cooks is common in community guesthouses in the Uatumã Sustainable Development Reserve, perpetrated by tourists who practice sport fishing. It is urgent to denaturalize these abuses, as well as to implement measures to prevent and combat harassment.

Photography by: Cecília Schwartz | Unsplash.

The Uatumã Sustainable Development Reserve (RDSU in the Portuguese acronym) is a protected area located in the state of Amazonas, in the Brazilian Amazon. The riverside communities of the RDSU have tourism as one of their main self-sustaining activities, whether through the sale of accommodation, food, and fishing services or the employment of cleaners, cooks, and pilots. Tourism is exclusively fishing tourism, with a predominantly male tourist participation, with rare attendance by women (usually daughters and wives). These tourists have high purchasing capacity and are predominantly white.

The kitchens of the rural community guesthouses at RDSU serve a dual purpose: to prepare meals for tourists, but also for the pilots, guesthouse employees, and the family itself, who own, work, and live in the vicinity of the lodge. We are talking about a kitchen that is, therefore, an extension of the family's domestic kitchen. All the cooks who work there are women. One might therefore think that harassment practices would be non-existent in this environment. However, this is not what our ethnographic work, part of a doctoral thesis, revealed.

Laborda (2024).

Kitchens of community rural guesthouses and cases of sexual harassment

A wall, with a passageway that is always open (there is no door), is what separates the kitchen from the common area where meals are eaten in the community guesthouses of the Uatumã Reserve. The common area is open to the public and shared by the family that owns the lodge, the tourism workers (the aforementioned pilots and guesthouse employees), and the tourists. For them, both places are seen as a single one. However, we noticed some divisions that, in this study, led us to choose to name the two areas separately. Thus, the kitchen is the place where meals are prepared. The common area is where people eat, drink, watch television and socialize.

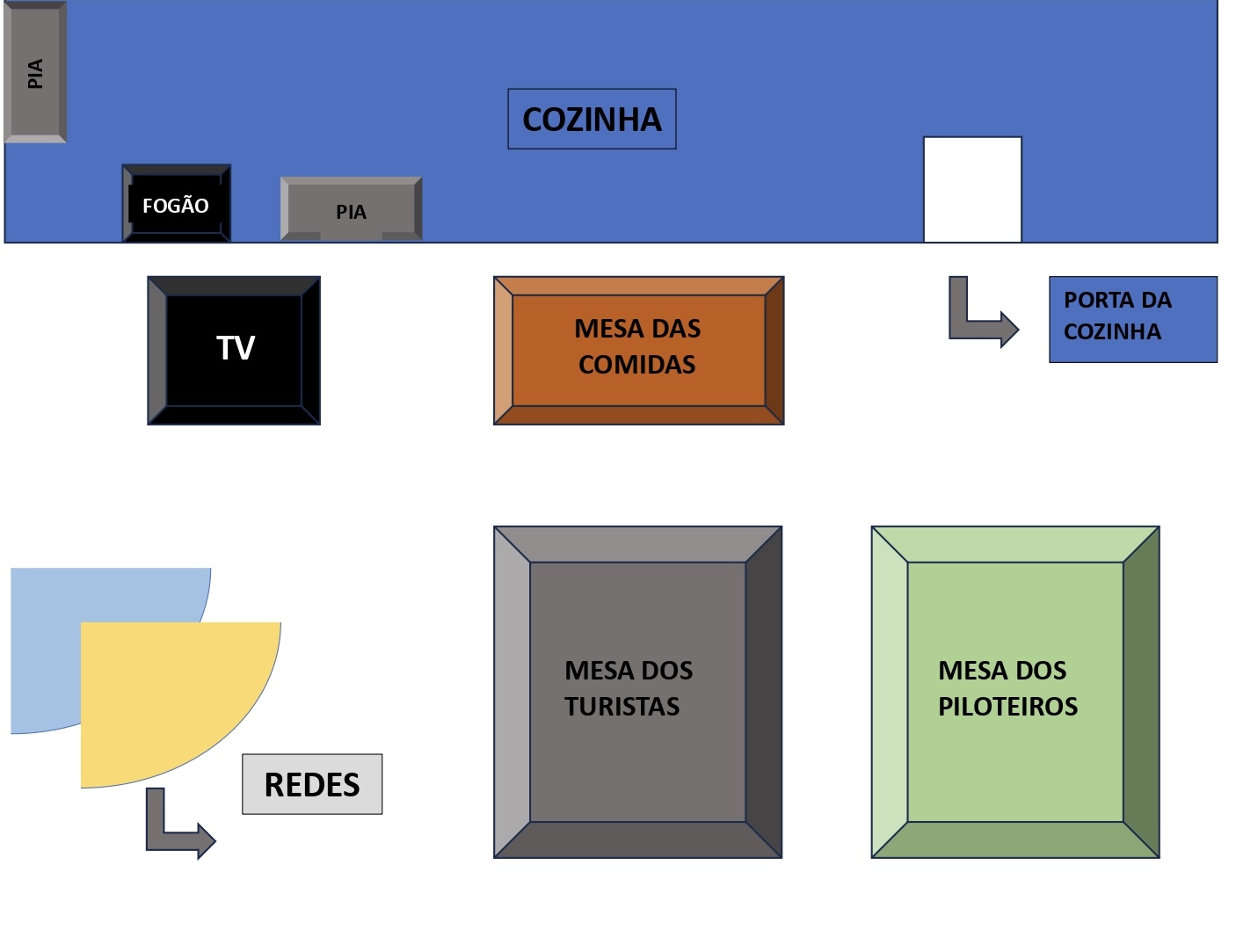

There are symbolic divisions noticed as one observes the place where each person sits and the moment they eat. Thus, there is a table for the pilots and a separated table for the tourists. At mealtime, the cooks place the food, plates and cutlery on a third table. The tourists serve themselves and sit at their table. The pilots, in turn, eat at a table next to them. The family and the rest of the workers (cooks and cleaners) eat before them or even after, when the tourists go to bed in their rooms before starting their afternoon fishing session.

Kitchen of the guesthouse. Source: Laborda (2023).

In the afternoon, when the children of the family that owns the guesthouse get home from school, they lie down in the hammocks that are also located in the space adjacent to the kitchen and only leave them in the early evening, when the tourists return from fishing. In the evening, this space becomes the main place for interaction between tourists, workers, and families, and the main focus is watching TV and accessing the internet, maintaining the territorial divisions, as shown in the following sketch.

In the kitchen, the work dynamic involves preparing breakfast, lunch, and dinner for tourists, workers, and the guesthouse owners, which is carried out by the cooks, under the supervision of the guesthouse owner's wife, who also cooks occasionally. The cooks are usually women from the community itself, but sometimes there are workers from Manaus who come exclusively to work in the sport fishing season.

Kitchen tasks are divided flexibly between cooks and helpers, creating a collective work environment that more closely resembles a domestic kitchen. This work dynamic, however, is affected by the presence of tourists, who occasionally walk through the kitchen. Their presence inside the kitchen should happen to satisfy punctual diet needs, but our fieldwork revealed the occurrence of sexual harassment in this context.

Sexual harassment is characterized by “constraint through words, gestures or acts with the aim of obtaining sexual advantage”(Amorim & Bueno, 2019, p. 157). The social and legal understanding of these and other abusive or violent practices has undergone cultural and historical variations (Almeida, 2019). The first mention of sexual harassment in the Brazilian penal code is recent: it dates back to 2001, and characterizes it as restricted to workplace context. Other practices, such as sexual harassment that occurs in the streets, are covered by the sexual importunity law, which dates back to 2018 (Almeida, 2019).

From the perspective of legal sociology, sexual harassment is analyzed as a manifestation of power and control relations within social and institutional structures. MacKinnon (1979) argues that sexual harassment is a practice that maintains and reinforces the subordination of women in the workplace and in other social contexts.

The layout of the kitchen in the community guesthouse. Laborda et al. (no prelo).

Gender studies, in turn, analyze how social norms and expectations related to gender influence both harassment behaviors and institutional responses to these complaints. Butler (1990) highlights that sexual harassment is a form of social control that reinforces traditional gender norms and male hegemony.

It is important to understand how recent the problematization of harassment and violence practices is and the understanding of these as something that should be criminalized because, in women's daily lives, it is still quite normalized. There is a lack of clear understanding of what constitutes harassment, and even the fear of retaliation and stigmatization (Wilness, 2007), as demonstrated by the episodes that we will discuss below.

Cases of harassment in the guesthouses surveyed occur very frequently inside the kitchen, in the sink and stove areas, where there is no visibility for those outside, and where the cooks spend most of their time. In this context, a cook told us that a tourist came into the kitchen after dinner and asked if she wanted to keep him company, as he was feeling lonely. He also said that he could help her financially, suggesting payment in exchange for sex. The kitchen has only one entrance and one exit, which even allows the workers to be “cornered” by the tourists.

However, harassment is not limited to the kitchen area, since when cooks serve food or move around the common area, they are also victims of tourists' advances. Thus, we witnessed harassment in the form of public compliments to the cooks, such as “what a beautiful brunette!”, “I didn't know there were such beautiful women in the Amazon”, comments that left the workers visibly embarrassed, as in the following example: “There are tourists who are more laid-back, and there are tourists who are all over us, they really suffocate us. [...] they ask us to be their girlfriends, they ask us to marry them. They offer money, and not a little!” (Cook at a community guesthouse in Uatumã, 23 years old, interview conducted in February 2023).

The dynamics of work in kitchens reveal numerous risks to which cooks are exposed, such as: physical and sexual violence, impacts on mental and physical health, such as depression, anxiety, stress, low self-esteem, headaches, gastrointestinal problems and tremors (Wilness et al., 2007). To avoid the cruel consequences, some strategies have been adopted.

Ongoing (non) confrontation strategies

We identified that, based on the cooks' externalization of the problem, the strategy used by the guesthouse owners to deal with this issue indicates they transfer the responsibility of curbing such practices to the employees themselves:

When Raul hires the girls, I speak very seriously to them, and so does Raul. We explain that they can't chat with tourists, that they have to be smart. They can't take anything into the rooms, they have to call the pilots or a man to take it. He avoids hiring the younger, more attractive girls, so as not to run any risks. We always prefer the older women, especially because they already have more experience (Mrs. Margarida, wife of the owner of a community guesthouse in Uatumã, 51 years old, interview conducted in February 2023).

Mrs. Margarida's comment, as is commonly seen in reports of cases of violence against women in different contexts, demonstrates an understanding that the victim is to blame for her appearance, as the owner “avoids hiring the younger, more attractive ones”. It therefore indicates a normalization of harassing behavior and the option to blame the victim of harassment instead of combating abuses committed by tourists,valuing customer satisfaction. Added to this is the lack of appreciation for the work of cooks, even though it is one of the fundamental stages of the tourist experience.

Laborda (2024).

In light of this, we have noticed collective strategies among workers to deal with harassment, such as the intentional presence of stewards in the kitchens until the women have finished their work. And whenever a woman realizes that another one is being cornered by a tourist, she tries to get closer so as not to leave her alone. The guesthouse is never without the presence of a male family member or a tourism worker. However,we must emphasize that these practices do not address the root of the problem: the harassing behavior of tourists. Therefore, we make some considerations about strategies that have been developed with this objective.

Strategic suggestions for overcoming harassment

Considering this scenario, we highlight the urgency of strategic measures regarding reporting, preventing and combating sexual harassment in the kitchens of community guesthouses. A cultural change is therefore necessary to denaturalize harassment practices and question traditional gender arrangements, especially with regard to the hegemonic masculinity model. In this sense, it is worth listing practical suggestions.

The suggestions listed here are inspired by the reflections of Picado e Martínez-Gayo (2022).Besides, there are collective suggestions listed by the first author of this study, who is organizing a tourism education plan with some tourism workers at RDSU.

In terms of prevention, we suggest educational programs for children and adults, especially guesthouse owners and workers, explaining the criminal nature of harassment and the measures available to victims and/or witnesses. In addition,it is necessary to dispel the idea that women are responsible for harassment, banning practices that blame victims, such as not hiring younger cooks; and eradicating the normalization of harassment disguised as flirting and compliments.

Above all, an educational program for tourists is needed, with monetary fines and zero tolerance rules, considering that workers have reported repeated harassment by the same tourists in different seasons. Therefore, we believe it is urgent that tourists attend lectures upon arrival at RDSU, and be informed about possible bans from future sport fishing seasons.

Furthermore, it is crucial to create an official reporting channel, which should impose sanctions from the first incident of harassment. Harassers can be permanently banned from sport fishing at RDSU and referred for legal accountability. This channel should have a specialized support team, including psychologists and psychiatrists.

Harassment practices are common in women's daily lives and, at the same time, violent and traumatic (Almeida, 2019), as evidenced in the testimonies of the cooks. These practices are often perpetrated by men associated to some extent with the hegemonic masculinity model. This is what urgently needs to change.

More Articles

-

Borja Suárez: “Vamos a la huelga general de hostelería en Santa Cruz de Tenerife”

General News | 17-04-2025 -

¿Turismo en el Parque Agrario de la Conca d’Òdena? Conocer para poder valorar

General News | 15-04-2025 -

Jornadas de mapeo: turismo, memorias y archivos

General News | 10-04-2025 -

Turistificación y malestares laborales: algo de memoria y futuro del sindicalismo en hostelería

General News | 08-04-2025 -

5º Seminario Perspectivas críticas sobre el trabajo en el turismo

General News | 25-03-2025