25-09-2024

World Tourism Day 2024: an opportunity for peace?

Alba Sud | Editorial«Tourism and Peace» is the theme UN Tourism chose to celebrate World Tourism Day on the 27th of September 2024. In a context in which armed conflicts and the culture of violence are spreading rapidly, it is necessary to ask ourselves, without preconceived ideas or triumphalism, what role the tourism industry is playing.

Photography by: Memoria y Tolerancia museum, CMX. Image from Ernest Cañada

The theme of the World Tourism Day promoted by UN Tourism September 27th of 2024 is Tourism and Peace. In the context of a sharp increase in armed conflicts that are once again bringing the planet to the brink, the proclamation sounds excessively voluntarist when only a series of benefits associated with this activity are mentioned. Reading that a world with more tourist visits would lead to more peaceful societies is unreliable. In this sense, it is argued that tourism can be a decisive and vital factor in fostering intercultural understanding, creating jobs, and stimulating sustainable development. However, in addressing this relationship between tourism and peace, it is crucial not to lose sight of the more complex and often contradictory realities of the role that global tourism plays today.

There is no peace in war

While UN Tourism announces new post-pandemic records in the number of international tourists, last June we reached another record high: the number of wars worldwide reached 56, with 92 countries involved; the highest peak of warfare since World War II.

To refer to peace today, in a world mired in violence, implies a moral and political commitment to end the wars and acts of genocide that plague the world. However, when approaching this issue with a modicum of empathy, only one word comes to mind: scandal. It is indeed scandalous what is happening in Gaza at the moment, where thousands of Israeli bombs are falling on Palestinian civilians and, in one year of war, more than 40,000 people have already been killed, including almost 14,000 children. The genocide being committed against the Palestinian people is of unspeakable dimensions.

Source: Demonstration in Barcelona, April 2024. Image from Pedro Mata | Fotomovimiento.

Likewise, the number of people killed and wounded in the war between Russia and Ukraine, three years after the start of the armed conflict, is already estimated at 500,000 people. Military defeat continues to be used as a way of resolving the conflict, which brings us to the risk of a nuclear war that threatens the very survival of humanity. And these are visible conflicts, which appear in the media, while in many other places crimes against humanity continue to take place without any attention being paid to them. In Africa, where much of the natural resources that are essential for the reproduction of capital are concentrated, armed conflicts are widespread. For example, the war in Sudan has already killed some 150,000 people, and there is a hunger crisis of displacement of historic proportions.

The reality of the world is far removed from sweetened visions in which tourism would be an antidote capable of favouring processes of pacification. On the contrary, we live on an increasingly violent planet, ecologically deteriorated, with societies that are increasingly unequal and exclusive, with territories that are more unequal and impoverished under the logic of touristification.

Tackling the contradictions of tourism

For UN Tourism, as presented in its declaration of 27 September, tourism would have such curative and prophylactic qualities that improve us as human beings and predispose us to be more peaceful and civilised. We don't know if they are inspired by the famous phrase of the Spanish writer Miguel de Unamuno when he said that "racism is cured by traveling". Sadly, we have never travelled so much, and yet racism is still present, and the violence it brings with it is only growing.

Tourism today is the result of a society with accelerated, hyper-consumerist lifestyles that generate as much inequality and social injustice as it does the deterioration of natural ecosystems. And this does not seem to improve the indices of human happiness at all.

In some countries, tourism generates significant economic income. However, its benefits are not evenly distributed. Large corporations and investment funds capture most of the benefits, while micro and small businesses and their workers, who are part of local communities, benefit the least and bear the brunt of the negative impacts. Furthermore, tourism is characterised as one of the sectors with the highest levels of precarious employment, also associated with a strong feminisation of its workforce. This dynamic perpetuates economic and social inequalities, contradicting the idea that tourism can be a tool for peace and equitable development.

On the other hand, tourism activity contributes, directly and indirectly, to generating environmental impacts. The construction of tourist infrastructures, the excessive consumption of natural resources, and just the generation of waste are some of the environmental problems associated with the touristification process. These impacts not only affect the local environment but also the well-being and livelihood of communities. Moreover, in some contexts, tourism can exacerbate existing conflicts or even create new ones. Land appropriation for tourism development, privatization of natural resources, commodification of culture, and displacement of residents are recurrent problems. The processes of tourism elitisation increase the dynamics of dispossession and inequality.

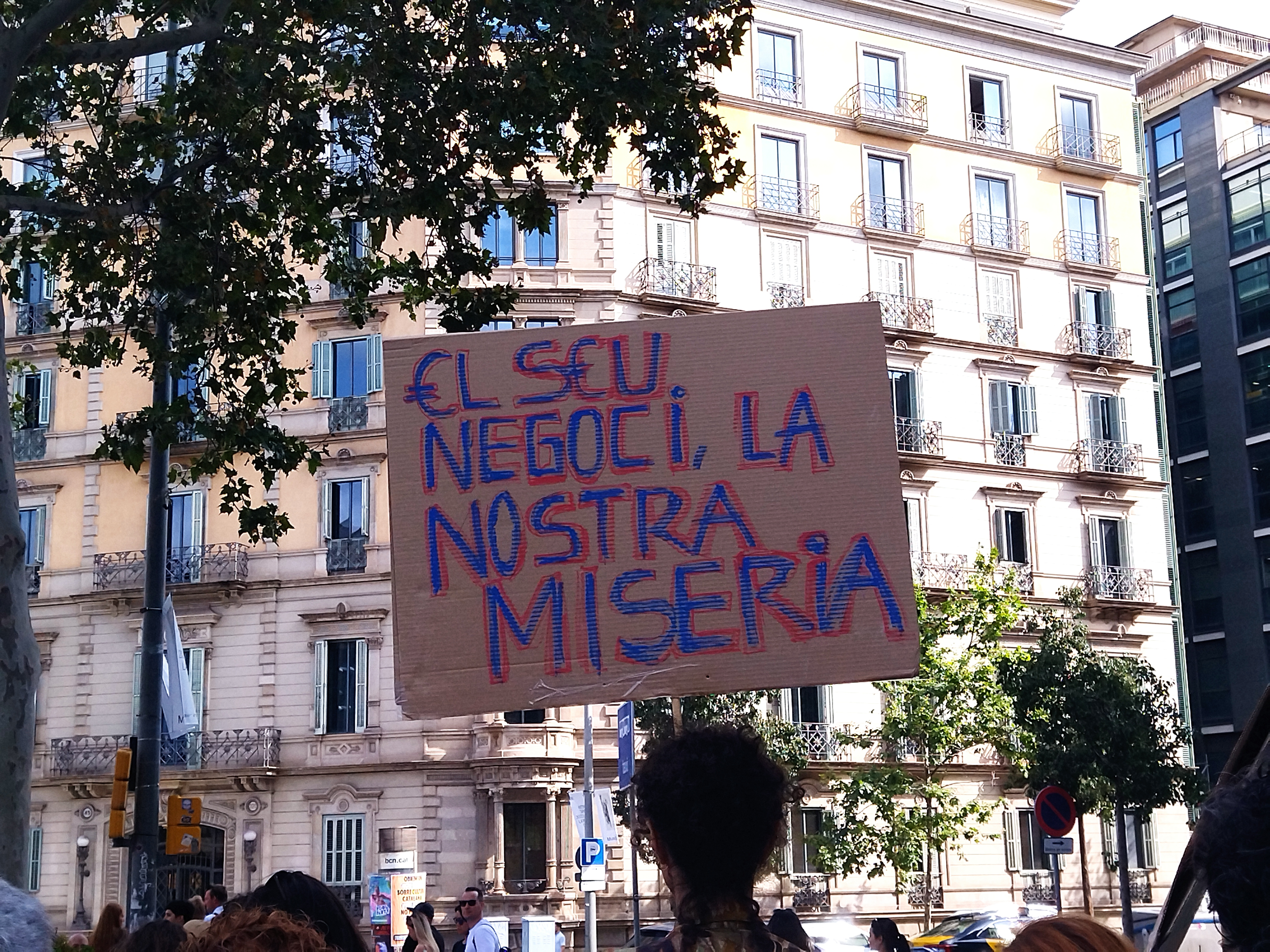

Source: Demonstration in Barcelona, July 2024. Image from Carla Izcara.

Additionally, tourism is also recurrently used by states committed to human rights violations and crimes against humanity as an instrument of propaganda and the projection of an image of normality. This is why more and more voices from social movements are calling for a boycott of products from these countries, including in the area of tourism consumption.

In short, there is no peace for those defending coastal areas or other fragile ecosystems from real estate projects and infrastructures that threaten environmental preservation. There is no peace for those who can no longer afford permanent housing because tourist rentals are more profitable, or to treat themselves to a coffee or lunch in a restaurant because the prices are for tourists. Nor is there peace for those who, working in the hotel and catering industry, suffer long hours, harassment, and union persecution and do not make ends meet, while their employers line their pockets.

However, we will not fall into the trap of establishing the opposite correlation and saying that more tourism means less peace and more war. This is not the case, and in a way, it would make us the mirror, also ridiculous, of what UN Tourism is doing with this statement. At Alba Sud, we defend that a completely different kind of tourism is possible to the mercantilist and destructive model in which we live and that has been expanded since the Second World War, which can be developed under totally different logic to those of the reproduction of capital.

Tourism, quality of life and social justice

While the idea that tourism can promote peace is appealing, it is important to approach this approach with some scepticism and discursive restraint. Peace is not achieved simply through cultural exchange and economic development. Building peace scenarios requires a continuous effort (De Villiers, 2014), and it is also a complex path, never to be conceived as finished, as many aspects can bring it to an end. Nothing in this process has to do with automatic solutions justified by economic interests of which little is known whether they will benefit most of the population. The mere fact of trying to promote a peace-related tourism activity will have to face numerous challenges: there may be different visions, and a lack of agreement, about the conflict or event, the trivialisation of it or the abuse of the term "peace" to commodify it (Alluri et al., 2014), among others. It therefore requires a deep commitment to social justice and equity. This implies re-evaluating current tourism practices and promoting models of community management and environmental preservation.

Tourism cannot be considered the cause of all ills nor can it solve all problems. There is a need for democratic planning under equity criteria, as well as public policies focused on improving the quality of life of the people who live in cities. There are no formulas; each territory, i.e. the groups, the groups, and institutions of each place, will have to define their priorities, problems and challenges. Tourism policy can accompany these strategies through social, associative, and community-based tourism programs, regulations, the creation of social infrastructures at the service of the majority, and the promotion of educational initiatives that accompany processes of historical reparation and memory against impunity, to cite just one example.

Source: SESC Bertioga.

Different public and associative experiences transcend the rhetoric of discourse to take their principles to the territory, to everyday management, and to guarantee more equitable and inclusive tourism practices, socially, economically, culturally, and environmentally. The social tourism programs implemented by the Argentinean government until the end of last year, the proposals of SESC São Paulo in Brazil, and the many community initiatives, reflect, among others, the contribution that certain forms of tourism organisation can make as a proposal for well-being, capable of promoting the activation of people and their environment and contributing to an improvement in the quality of life and the generation of new skills in the fields of culture, nature, and sport. In these contexts, the practice of tourism constitutes an opportunity to generate historical, ecological, and community awareness; to configure new models of social behaviour, more respectful of communities and their environment. Tourism that, in short, favours experiences that are experiential, slow, and empathetic with the local populations, their histories, gastronomy, and nature. At Alba Sud, we are convinced that if tourism can contribute to peace in any way, it must have these characteristics. We do not say it is easy, but we firmly believe it is worth the effort.

The development model defended by UN Tourism is the product of a capitalist society that devours and destroys nature, generates injustice, inequalities, and consequently, violence and wars. In a society built based on equality, justice, solidarity, and peace with the planet, we must construct another form of tourism, and we can recognise the existing experiences, even if they are in the minority. This other form of tourism has to be based on human needs for well-being, health, relaxation, and personal development. Also, it has to be relocated mainly in geographical proximity to places of residence. We hope that its implementation can contribute to a world with peace, equity, and social justice.

More Articles

-

Últimos paraísos. Urbanización del espacio rural y resistencia social en el Pueblo Mágico de Sisal, Yucatán

General News | 24-04-2025 -

Borja Suárez: “Vamos a la huelga general de hostelería en Santa Cruz de Tenerife”

General News | 17-04-2025 -

¿Turismo en el Parque Agrario de la Conca d’Òdena? Conocer para poder valorar

General News | 15-04-2025 -

Jornadas de mapeo: turismo, memorias y archivos

General News | 10-04-2025 -

Turistificación y malestares laborales: algo de memoria y futuro del sindicalismo en hostelería

General News | 08-04-2025